Forced to fight

Amid recent farmers’ protests, a Harsola activist works to support agricultural workers and reduce the suffering of those in his community.

By Sarah Bakeman

Jasvinder Dhull stands outside his Harsola home on a hazy January day after returning from the Kisan Mazdoor Canteen. He lives in the house with his wife, his mother and his two sons. “My sons are now almost as tall as me. I believe they’ll live long and well,” Jassi said. “I’ve kept my family safe. If something were to happen to me, I hope and believe that they’ll take my place.” | Photo by Sarah Bakeman

Jasvinder Dhull’s buzzing phone interrupted his afternoon nap with a sequence of WhatsApp notifications. Fellow Harsola residents’ frantic messages came together to create a clear picture: A neighbor’s wheat farm was burning, and the fire was spreading quickly. Jassi rounded up his 8-year-old son and the two headed toward the flames.

From the back of the motorcycle, the boy asked a question: “If the whole field is burned, how will the farmer’s children buy books for their education?”

Although Jassi and other residents were able to extinguish the fire before the damage was too devastating, the boy’s question lingered for Jassi. If a child could recognize the volatility of agriculture work in India, it must be important.

Jassi is not a farmer, but he knows what land means. He knows if a wheat field burns or a land-dispute court case is lost, a livelihood goes with it. He knows it takes protesting, tractor parades, refusing government bribes and sometimes jail time to protect those who cultivate the soil. He knows that at its best, land provides for children, and at its worst, land moves men to murder.

_____

Jassi draws from his own difficult past to inspire the goal behind his farm activism: minimize human suffering.

Farming is central to life in Harsola, a village of 5,000 people. According to the Haryana Department of Agriculture and Farmers, 70% of residents depend on agriculture for their livelihood, and the majority of farms are small-scale and family-owned. Land is the single most important household asset and determinant of wealth.

“I know that the land will take care of me even if I am not successful,” Jassi said.

Jassi is one of the many whose inheritance was family land — 10 acres of Harsola earth from his paternal grandfather, Ram Sarup. Jassi, however, did not inherit the knowledge of how to cultivate it. Other working-class farmers spent their childhoods weeding out rice paddies, collecting and watering from a tube well and gathering harvested bundles of wheat. But Jassi spent much of his childhood at a boarding school, an hour away from his birthright.

He was enrolled in seventh grade by his grandfather and maternal uncle, who repeatedly cited the importance of education. But Jassi knew that beneath their talk of classes and opportunities, boarding school was an act of protection. He would be away from his home village of Harsola. That’s where his father, Sewa Singh, could find him.

“There was never a connection between us,” Jassi said. “Our relationship was always shattered.”

_____

Here is Jassi’s version of his origin story: Before he was born, his father left their family to be with another woman. His mother, Kelovati, became a six-months-pregnant, soon-to-be single parent. She had to make a decision: abort the child and remarry, providing stability in a patriarchal society, or keep her child and remain a somewhat-shunned single mother. She chose to raise Jassi.

By the time Jassi was a teenager, Sewa would make occasional returns to Harsola. The visits were quickly soured by death threats and a visible pistol in the man’s pocket. Sometimes he came alone, and sometimes he came with friends who backed his threats with more words and pistols.

“He used to come into our lives just to create a mess,” Jassi said. “He never thought of me as a son.”

Sewa wanted the 10 acres that belonged to his father. But he knew the land was to be passed down to Jassi, and he would kill his own son to get it.

Boarding school could provide distance and protection, Jassi’s grandfather hoped.

While Jassi’s removal from Harsola eased his family’s fears, he felt his own anxiety worsen. Between the school’s pink-painted cement walls, Jassi thought about his grandfather dying — either by natural causes or by murder. He thought about his father claiming the land in his absence. And he thought about himself — how he’d be working on his handwriting or studying for a math exam, unaware of the drama playing out an hour away.

“If my father were to kill my grandfather, he’d get everything,” Jassi said. “My mother’s sacrifice would be for nothing.”

Education couldn’t provide survival, Jassi thought. Only land could do that. At 16, after three years at boarding school, he returned home.

“People told me not to leave my school. It’s a good school and not everybody gets an opportunity to study there,” Jassi said. “But I was worried about my land and my grandfather. I had to come home.”

Throughout 11th and 12th grade, Jassi reconnected with the village. He made friends with boys his age, deepened his relationship with his mom and grandfather and felt more supported than ever before. If Sewa came with friends and pistols, Jassi says his own friends would come to his house in a group. Jassi remained safe for three years.

That’s when Sewa attempted to murder Jassi’s grandfather.

When Ram felt a firm push on his back and the concrete slipping beneath his feet, he realized Sewa’s threats were no longer empty. Ram was standing on his roof, next to a ledge and a 20-foot drop. He caught himself and yelled for his son-in-law to help. Although Sewa’s attempt failed, it was unclear how, when and if he would attack again. Jassi’s grandfather decided to transfer ownership of the land to Jassi.

_____

Instead of following through on threats of physical violence against his son, Sewa brought his grievances to India’s legal system. He claimed the land rightfully belonged to him, arguing it was ancestral, not self-acquired. In other words, he said the land should be distributed between all family members — Ram had no right to give it to Jassi.

A string of three civil cases ensued, lasting from 2006 to 2018. Starting when he was 24 years old, Jassi spent over a decade in and out of hearings. He called it a full-time job, where his father stood across the courtroom with that familiar pistol glinting in his pocket.

“He kept filing cases against me,” Jassi said. “One after another. He never tried to make amends. He was always against us.”

In response, Jassi bought a pistol of his own. He kept it hidden underneath his shawl most of the time. He says he didn’t buy it to be pointed or shot. Instead, when Jassi moved the fabric of his shawl to reveal the weapon to his father, he hoped to send a message.

You may be strong, but so am I.

Jassi’s friends did the same with their own pistols, often coming to the courtroom to show support during those 12 years.

“The best moment for me was when my friends stood by me,” Jassi said. “They had no greed. They knew I could get shot at any point.”

“The best moment for me was when my friends stood by me.”

Jassi’s extended time in court can be chalked up to India’s notoriously backed-up judiciary. The delays are largely due to a low judge-to-population ratio. According to The New York Times, there are 50 million court cases pending in the country. At the current rate of court system proceedings, these cases would take 300 years to clear.

Among these pending cases, land and property disputes account for the largest fraction.

During his 12 years in court, Jassi’s first wife committed suicide, he was remarried and then had two sons with his second wife. With all that happened in that time, his case was still completed eight years sooner than the average land dispute.

Jassi won his maternal family’s 10 acres 16 years after the attempt on his grandfather’s life. Nonetheless, Jassi celebrated. He felt this victory would not only provide for his family, but recompense the sacrifices his mother made in choosing to birth and raise him, as well as the time his friends spent supporting him in and out of the courtroom.

“I thought it didn’t matter how the world was against me as long as my mother, grandfather and family stood by me,” Jassi said.

_____

Instead of farming, Jassi supports his family by contracting his land to small-scale wheat and rice farmers, who use their profits to support their own families. While those families till and harvest from his inheritance, Jassi concerns himself with protesting for their rights. Often, Jassi says the Indian government does not act in favor of family farmers or the labor class that works in the fields.

During his court case and after, he would think back to the childhood years when he felt scared and oppressed by Sewa’s threats. His mother would repeat an affirmation to him.

“Our time will come when we will be happy,” she would say. “Now, I want you to be a good citizen, and I want you to help others.”

Jassi says he felt obligated to take an active role in farmers’ protests, a story that has dominated Haryana and all of India for the last four years. At first he showed up as a listener, furious note-taker and chanter in the crowd, and later as the man speaking into the microphone.

“Whenever he sees bad things happening to people, he just wants to help,” Kelovati said.

_____

In 2015, Jassi helped organize a protest in Titram, 5 kilometers from his home, in which demonstrators were on the street 24 hours a day for 49 days. The action sparked after the Haryana government announced a plan to build a highway that would travel across eight villages in the Kaithal area. The proposed road would cut through the farmers’ lands — earth inherited through generations even before English colonialism — and landowners would receive 27 lakhs INR ($32,500) per acre. This was not the fair value of the land.

The same year as the protest, Indian politician Shanta Kumar chaired a committee on the restructuring of the Food Corporation of India. The FCI is in charge of maintaining the minimum support price for crops in India, a safety net for farmers. This MSP guarantees farmers will earn a certain level of income for their crops and won’t experience losses. The United States Department of Agriculture does the same thing for American farmers.

But the Shanta Kumar Committee Report revealed a new truth. Only 6% of Indian farmers received the government’s guaranteed MSP for their crops. And now, Kaithal-area farmers were being offered less than the standard value for the land.

They were tired of not receiving their fair share.

Although the event started with about 40 people, the protest grew to more than 10,000 frustrated farmers shouting from carts and flatbed trailers. Police tried repeatedly to break up the demonstration through bribery or threatening legal action. Some protesters were offered new cars in exchange for compliance, something Jassi says is common for him. Basically, a local government official would offer Jassi or other organizers their choice of vehicle. A non-luxury car can cost up to 52 lakh ($65,000).

In the end, the government raised its offer price to 47 lakhs per acre, almost double the original offer. This deal was the fair value of the land, Jassi said with a toothy smile.

Jassi still drives to protests on his motorcycle.

_____

In 2018, Jassi’s court case was completed. As he drove down village roads with friend and fellow activist Kumar Mukesh, the man asked him a question.

“What do you want to do now?”

Jassi knew the answer. He wanted to be a leader and political activist for farmers in Haryana. And now, he could do it without worrying about court dates or unwanted interactions with Sewa or stress about lawyers and finances.

“After I won my land, my family had something to fall back on. Then I had the confidence to go out and work for others.”

“After I won my land, my family had something to fall back on,” Jassi said. “Then I had the confidence to go out and work for others.”

A few weeks later, Jassi set off from Kaithal with a band of 16 farmers and seven tractors for another protest. The group was Delhi-bound, with a plan to pick up more farmers along the 184-kilometer route. If everything went according to plan, the group would arrive in the capital and demonstrate to bring attention to the 2004 Swaminathan Report written by the National Commission on Farmers.

The report is mostly economic in content, as it details recommendations for enhancing the profitability and sustainability of farming in India through selling price protection. Despite talk of profits and losses, the report wasn’t solely about boosting farmers’ bank accounts. It was rooted in a concern for how the monetary stress of agricultural work in India contributes to high farmer suicide rates.

Fourteen years after the report’s original release, that same concern remains.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau, a government intelligence agency, 10,600 farmers and agricultural laborers committed suicide in 2020 — a number Jassi believes to be inaccurate. He suggests that the rate is much higher, but downplayed by the government to ease farmer uprisings.

Jassi isn’t alone in a growing skepticism surrounding government statistics. During the 2023 G20 Summit, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s failure to conduct the 2020 census, a process that has been delayed nine times, faced criticism. India is the only G20 country that has not completed the census. Additionally, Indian National Congress leader Jairam Ramesh spoke at the summit, saying that the Modi government “discredits, discards or even discontinues collecting any data that it finds inconvenient to its narrative.”

During the 2018 protest, Jassi and the farmers drove their seven tractors as far as Hisar, 124 kilometers southwest of Kaithal, before they were stopped by police. Jassi was jailed for seven days in Kaithal.

In 2019, they tried the same protest again, with the same hope of calling attention to the report and farmer suicides. This time, they made it to Kailram, only 15 kilometers south of Kaithal. Again, they were confronted by police, and Jassi was jailed for another seven days.

_____

May 15, 2020, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced the introduction of three farm bills. These bills, if made into law, would reshape agriculture for India’s 150 million smallholder farmers and their dependents.

The goal behind the bills was simple: change India’s agricultural sector from public-run to private-run. In other words, minimize the government’s role in farming and open up room for private investors.

Modi and government-controlled media said the market-friendly bills would bring growth.

“The bigger media houses were bought off,” Jassi said. “They portrayed these bills as something that would double or triple a farmer’s income.”

Many farmers opposed the bills, stating they would eliminate state protections and regulatory support, such as the already-insufficient MSP protections. Smallholder farmers would be left under the heel of large, for-profit corporations who would now decide the minimum price.

Other farmers didn’t even know the bills existed. And some knew about them, but couldn’t read them — they were originally only published in English.

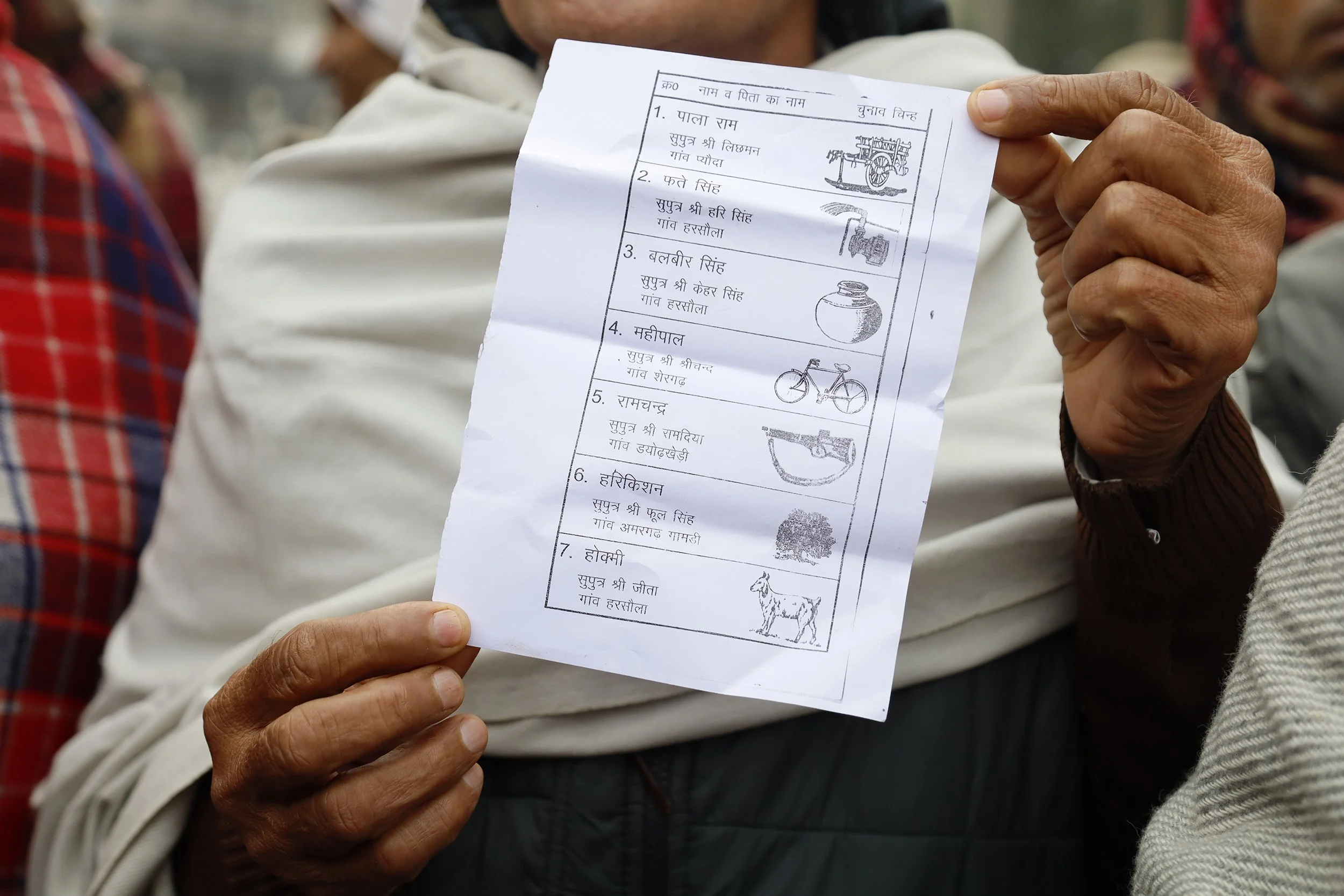

After farmers’ union leaders translated the bills into Hindi and Haryanvi, Jassi and fellow farmers’ activists decided to spread the word. For the most part, Punjabi farmers were aware of what was happening. Haryana’s farmers were not. From village to village, Jassi talked about the three bills, what they meant and how they would impact people.

21

judges per million

people in India150

judges per million

people in AmericaSource: The New York Times

“These bills are going to kill you,” Jassi would conclude.

Sept. 27, 2020, the bills became law.

In the month that followed, Jassi protested locally alongside activists and farmers, chanting on streets and posting clips of the gatherings to Facebook to spread the word. Similar protests spread across the whole of Haryana and Punjab. But after two months, the phrase Dilli chalo, translating to “Let’s go to Delhi,” was repeated from protester to protester.

In November, Jassi attended a rally in Pipli, a village 6 kilometers from the Haryana-Delhi border. Like the tractor protests that preceded, the goal was to go to the nation’s capital, this time using the national highway that connected Pipli to Delhi. Thousands gathered, the majority of them men. Some took the road by tractor or truck, but the bulk of the protesters moved on foot, cheering and chanting as men spoke into megaphones.

Not long into the rally, the police showed up and beat protesters. Requests to march the capital city had been denied, with the Delhi police citing COVID-19 protocols.

Jassi then relocated to the Punjab-Haryana border, where another Dilli chalo movement was starting. As thousands of farmers made their way south, they were met with water hoses and tear gas, sent over police barricades. Nov. 25 ended with protesters breaking through barricades and Delhi police officers allowing entrance into the capital for a peaceful protest. This kicked off the 2020 Indian farmers’ protest.

The demonstrations lasted for a year, with thousands of farmers and activists, including Jassi, setting up self-sufficient camps in the capital. Rows of tents and tarps lined highways through a bitter winter and scorching summer. Children and elders alike huddled inside, fixing their tents after windy days and swatting away mosquitos on humid nights. Food was supplied from farmers back home, primarily in Haryana and Punjab. Water was gathered, laundry done and meals cooked, all in these temporary settlements.

In those 13 months, 750 people died on the streets. Most of these deaths were due to natural causes. Many of the farmers protesting were elderly, fighting for the only livelihood they had known, passing away in tents far from their land.

“People did not care if they were to live or die during the protest. They wanted to win,” Jassi said. “That’s what made me realize that we’ll win this fight.”

Jassi stayed in Delhi for seven months before he returned home. For the remaining five months, he split his time between Harsola and Delhi.

“I want to do something for my village and for my society. I want to be proud of what I do.”

It became clear that the protesters, who continued to collect a steady income of food and donations for their villages, were not letting up. Additionally, important elections for Modi’s party were coming up in 2022.

Oct. 29, 2021, Modi spoke for four minutes in a televised address to the nation.

“Main aaj deshavaasiyon se kshama maangate hue,” he said.

“Today, I apologize to my countrymen.”

Modi followed this with an announcement: the three farm laws would be repealed. He then advised farmers and activists to take down their tents and return to their homes.

On the streets, some protesters ate Jalebi, an orange coil of fried maida flour. Music played and men danced with their arms reaching out over their heads, firecrackers popping on the pavement they had called home. But others refused to take their tents down. They wanted to see a formal repeal of the laws before packing up and leaving for good.

Jassi celebrated alongside the men, but later became philosophical.

“We are forced to fight,” Jassi said. “We don’t want to protest. We don’t want to die on the streets. We don’t.”